Jason Sheltzer

@JSheltzer

Followers

18K

Following

7K

Media

970

Statuses

5K

Assistant prof at @StanfordMed. Interested in aneuploidy, mitotic kinases, cancer therapeutics, and drug development. Co-founder x2.

Joined February 2016

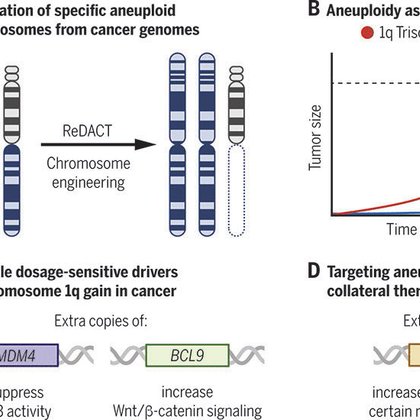

Check out our new study in @ScienceMagazine, where we take on a 100-year-old debate: what’s the role of aneuploidy in cancer? We discovered that genetically removing extra chromosomes blocks cancer growth - a phenomenon we call “aneuploidy addiction”.

science.org

Specific aneuploidies benefit cancer cells and may be sensitive to treatment

47

340

1K

Important bridge funding mechanism from @AmericanCancer for early career investigators with high-scoring, but unfunded research projects to either ACS or NCI. ACS Catalyst Awards: https://t.co/0h9BD1FjNF

cancer.org

0

7

25

Amazing progress from @medra_ai. In biology, there's a limit to how far you can get with LLMs alone. At some point, you need to get into the lab and do an experiment. I strongly believe that high-quality robots generating high-quality data will greatly accelerate bio discoveries.

1

1

21

This project will build on our recent publication in which we studied the consequences of chromosome 8p alterations in engineered iPS cells and characterized its effects on gene expression and neural differentiation: https://t.co/o46UzpvQzx.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Chromosomal rearrangements on the short arm of Chromosome 8 cause 8p syndrome, a rare developmental disorder characterized by neurodevelopmental delays, epilepsy, and cardiac abnormalities. While...

0

0

3

I’m excited to share a new postdoctoral opportunity in my lab at Stanford to study the consequences of gene dosage alterations in iPS cells. Check out the posting below and shoot me an email if you’re interested -

2

46

144

This work was led by Kaitlin Long, a phenomenal undergrad/tech in my lab. Many of you reading these tweets received a PhD application from her over the weekend! I cannot emphasize enough what an exceptional scientist she is - I think that any lab would be lucky to have her join.

3

0

18

Additionally, we think that PAC-1 could have significant utility as part of a broader combination-therapy regimen, to delay or reverse MDR1 activation and enhance tumor sensitivity to SOC chemotherapies.

1

0

6

Excitingly, PAC-1 has entered clinical testing, where it has been well-tolerated and resulted in multiple patient responses. However, no biomarker capable of predicting sensitive tumors was reported. We think that MDR1 expression could be the missing biomarker.

1

2

9

Critics say Israel is a liability—but facts show it’s America’s strategic shield. These 5 reasons reveal its vital role in defense, intel & stability. Watch the full video to see why Israel matters.

40

48

233

How is this possible? We found that PAC-1 is being effluxed by MDR1 - but PAC-1 bound to iron is effluxed much more rapidly than PAC-1 by itself. So, MDR1 activity doesn't protect cells - it accelerates iron starvation in MDR1-high cells by pumping out the drug-iron complex.

1

0

7

We also found that we could use PAC-1 to reverse this process: we took chemo-resistant, MDR1-high cells and cultured them in PAC-1 for a few weeks, and we found that this resulted in a 20-fold decrease in MDR1 expression and a 7-fold increase in chemotherapy sensitivity.

1

0

5

Similarly, evolving cancer cells in chemotherapy causes MDR1 upregulation and resistance to a broad range of anti-cancer. But, these evolved drug-resistant cells exhibited significant collateral sensitivity to PAC-1.

1

0

5

To confirm this association, we generated MDR1-KO clones and we verified that these cells were more sensitive to standard chemotherapies, as we expected. However, we also found that the chemo-resistant MDR1-high cells were much more sensitive to PAC-1 than the MDR1-KO cells!

1

1

7

RKLX offers 200% daily exposure to the share price movements of RKLB. Investing involves risk. Principal loss is possible. Defiance Daily Target 2X Long RKLB ETF is distributed by Foreside Fund Services LLC. Read the prospectus at

0

0

9

Surprisingly, using PRISM, we found that the cells most sensitive to PAC-1 were over-expressing MDR1 (also called P-gp). MDR1 stands for MultiDrug Resistance 1: it’s an efflux pump that expels drugs from tumors. But our data suggested that MDR1 conferred PAC-1 sensitivity!

1

1

5

We used the PRISM dataset from @corsellos and found that PAC-1 was behaving like an iron-chelation agent. We confirmed that PAC-1 depleted cellular iron, upregulated an iron-starvation transcriptional response, and PAC-1 lethality could be reversed with iron supplementation.

1

0

5

The drug is called PAC-1. It was initially developed to target cancer cells by activating the executioner caspases. But, we generated CASP3/6/7 triple-knockouts and it still eliminated cancer cells, demonstrating that it must have some other target.

1

1

15

New from my lab on bioRxiv - we found an existing drug that appears to be safe in humans that selectively kills chemotherapy-resistant cancer cells.

A clinical-stage oncology compound selectively targets drug-resistant cancers https://t.co/BLuaVqxwlO

#biorxiv_cancer

7

50

346

My former student Ann Lin is hiring engineers for her fast-growing start-up @CromaticHQ! Building software to help scientific outsourcing and connect research labs with the best service providers. Check it out below -

2

0

3

For a flat $10k fee, I will tweet the following the next time your company drops a SOTA model: “Wow! My lab received advanced access to [your company]’s [model name], and it’s totally exceeding all of our scientific benchmarks!”

7

11

119

I love biotech but I don't think that biotech is capable of completely replacing academic research - https://t.co/ViZAV0MlaX

statnews.com

Exclusive: Arena Bioworks, the buzzy research institute that launched with $500 million to support a decade of scientific R&D, is abruptly shutting down, STAT has learned.

Many incredible biomedical scientists have left academia for biotech/pharma. While also noting many caveats, I want to share the observation that among top scientists who left academia for industry, their biggest new discoveries almost always happened in academia:

16

11

141

Many academic disciplines have famous geographic divisions- In economics, freshwater (midwestern, free-market) vs. saltwater (coastal, Keynesian) In philosophy, continental (European, Kantian) vs. analytical (British, logical) Do any geographic divisions exist in biomedicine?

3

0

10